Bruteforce Login Prevention

- Bruteforce Login Prevention Plan

- Bruteforce Login Prevention Mikrotik

- Brute Force Login Prevention 2017

How to stop/prevent SSH bruteforce closed Ask Question 20. Best way to prevent brute force logons? Don't let them get to your machine in the first place! There are plenty of ways to stop brute force attempts before they get to your host, or even at the SSH level. Fail2ban can be configured to monitor any service that writes login. We recently suffered a brute force login attack on one of my servers which was causing some sites to be unreachable and the server load was sky-high. After installing a logging script on the server we found out that the problem was caused on one installation of WordPress – hackers were using a.

In cryptography, a brute-force attack consists of an attacker submitting many passwords or passphrases with the hope of eventually guessing correctly. The attacker systematically checks all possible passwords and passphrases until the correct one is found. Alternatively, the attacker can attempt to guess the key which is typically created from the password using a key derivation function. This is known as an exhaustive key search.

A brute-force attack is a cryptanalytic attack that can, in theory, be used to attempt to decrypt any encrypted data[1] (except for data encrypted in an information-theoretically secure manner). Such an attack might be used when it is not possible to take advantage of other weaknesses in an encryption system (if any exist) that would make the task easier.

When password-guessing, this method is very fast when used to check all short passwords, but for longer passwords other methods such as the dictionary attack are used because a brute-force search takes too long. Longer passwords, passphrases and keys have more possible values, making them exponentially more difficult to crack than shorter ones.

Brute-force attacks can be made less effective by obfuscating the data to be encoded making it more difficult for an attacker to recognize when the code has been cracked or by making the attacker do more work to test each guess. One of the measures of the strength of an encryption system is how long it would theoretically take an attacker to mount a successful brute-force attack against it.

Brute-force attacks are an application of brute-force search, the general problem-solving technique of enumerating all candidates and checking each one.

Bruteforce Login Prevention Plan

Basic concept[edit]

Brute-force attacks work by calculating every possible combination that could make up a password and testing it to see if it is the correct password. As the password's length increases, the amount of time, on average, to find the correct password increases exponentially.

Theoretical limits[edit]

The resources required for a brute-force attack grow exponentially with increasing key size, not linearly. Although U.S. export regulations historically restricted key lengths to 56-bit symmetric keys (e.g. Data Encryption Standard), these restrictions are no longer in place, so modern symmetric algorithms typically use computationally stronger 128- to 256-bit keys.

There is a physical argument that a 128-bit symmetric key is computationally secure against brute-force attack. The so-called Landauer limit implied by the laws of physics sets a lower limit on the energy required to perform a computation of kT· ln 2 per bit erased in a computation, where T is the temperature of the computing device in kelvins, k is the Boltzmann constant, and the natural logarithm of 2 is about 0.693. No irreversible computing device can use less energy than this, even in principle.[2] Thus, in order to simply flip through the possible values for a 128-bit symmetric key (ignoring doing the actual computing to check it) would, theoretically, require 2128 − 1 bit flips on a conventional processor. If it is assumed that the calculation occurs near room temperature (~300 K), the Von Neumann-Landauer Limit can be applied to estimate the energy required as ~1018joules, which is equivalent to consuming 30 gigawatts of power for one year. This is equal to 30×109 W×365×24×3600 s = 9.46×1017 J or 262.7 TWh (more than 1% of the world energy production).[citation needed] The full actual computation – checking each key to see if a solution has been found – would consume many times this amount. Furthermore, this is simply the energy requirement for cycling through the key space; the actual time it takes to flip each bit is not considered, which is certainly greater than 0.

However, this argument assumes that the register values are changed using conventional set and clear operations which inevitably generate entropy. It has been shown that computational hardware can be designed not to encounter this theoretical obstruction (see reversible computing), though no such computers are known to have been constructed.[citation needed]

As commercial successors of governmental ASIC solutions have become available, also known as custom hardware attacks, two emerging technologies have proven their capability in the brute-force attack of certain ciphers. One is modern graphics processing unit (GPU) technology,[3][page needed] the other is the field-programmable gate array (FPGA) technology. GPUs benefit from their wide availability and price-performance benefit, FPGAs from their energy efficiency per cryptographic operation. Both technologies try to transport the benefits of parallel processing to brute-force attacks. In case of GPUs some hundreds, in the case of FPGA some thousand processing units making them much better suited to cracking passwords than conventional processors.Various publications in the fields of cryptographic analysis have proved the energy efficiency of today's FPGA technology, for example, the COPACOBANA FPGA Cluster computer consumes the same energy as a single PC (600 W), but performs like 2,500 PCs for certain algorithms. A number of firms provide hardware-based FPGA cryptographic analysis solutions from a single FPGA PCI Express card up to dedicated FPGA computers.[citation needed]WPA and WPA2 encryption have successfully been brute-force attacked by reducing the workload by a factor of 50 in comparison to conventional CPUs[4][5] and some hundred in case of FPGAs.

AES permits the use of 256-bit keys. Breaking a symmetric 256-bit key by brute force requires 2128 times more computational power than a 128-bit key. Fifty supercomputers that could check a billion billion (1018) AES keys per second (if such a device could ever be made) would, in theory, require about 3×1051 years to exhaust the 256-bit key space.

An underlying assumption of a brute-force attack is that the complete keyspace was used to generate keys, something that relies on an effective random number generator, and that there are no defects in the algorithm or its implementation. For example, a number of systems that were originally thought to be impossible to crack by brute force have nevertheless been cracked because the key space to search through was found to be much smaller than originally thought, because of a lack of entropy in their pseudorandom number generators. These include Netscape's implementation of SSL (famously cracked by Ian Goldberg and David Wagner in 1995[6]) and a Debian/Ubuntu edition of OpenSSL discovered in 2008 to be flawed.[7] A similar lack of implemented entropy led to the breaking of Enigma's code.[8][9]

Credential recycling[edit]

Credential recycling refers to the hacking practice of re-using username and password combinations gathered in previous brute-force attacks. A special form of credential recycling is pass the hash, where unsalted hashed credentials are stolen and re-used without first being brute forced.

Unbreakable codes[edit]

Certain types of encryption, by their mathematical properties, cannot be defeated by brute force. An example of this is one-time pad cryptography, where every cleartext bit has a corresponding key from a truly random sequence of key bits. A 140 character one-time-pad-encoded string subjected to a brute-force attack would eventually reveal every 140 character string possible, including the correct answer – but of all the answers given, there would be no way of knowing which was the correct one. Defeating such a system, as was done by the Venona project, generally relies not on pure cryptography, but upon mistakes in its implementation: the key pads not being truly random, intercepted keypads, operators making mistakes – or other errors.[10]

Countermeasures[edit]

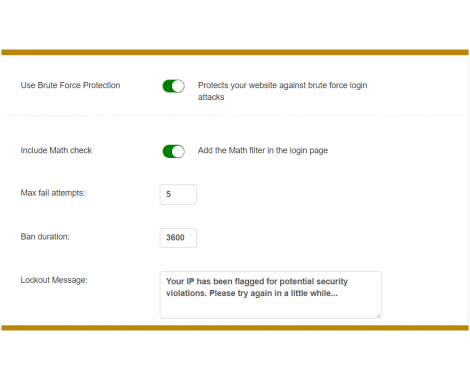

In case of an offline attack where the attacker has access to the encrypted material, one can try key combinations without the risk of discovery or interference. However database and directory administrators can take countermeasures against online attacks, for example by limiting the number of attempts that a password can be tried, by introducing time delays between successive attempts, increasing the answer's complexity (e.g. requiring a CAPTCHA answer or verification code sent via cellphone), and/or locking accounts out after unsuccessful logon attempts.[11][page needed] Website administrators may prevent a particular IP address from trying more than a predetermined number of password attempts against any account on the site.[12]

Reverse brute-force attack[edit]

In a reverse brute-force attack, a single (usually common) password is tested against multiple usernames or encrypted files.[13] The process may be repeated for a select few passwords. In such a strategy, the attacker is generally not targeting a specific user.

Software that performs brute-force attacks[edit]

See also[edit]

- TWINKLE and TWIRL

Notes[edit]

- ^Paar 2010, p. 7.

- ^Landauer 1961, p. 183-191.

- ^Graham 2011.

- ^Kingsley-Hughes 2008.

- ^Kamerling 2007.

- ^Viega 2002, p. 18.

- ^CERT-2008.

- ^Ellis.

- ^NSA-2009.

- ^Reynard 1997, p. 86.

- ^Burnett 2004.

- ^Ristic 2010, p. 136.

- ^'InfoSecPro.com - Computer, network, application and physical security consultants'. www.infosecpro.com. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved May 8, 2018.

References[edit]

- Adleman, Leonard M.; Rothemund, Paul W.K.; Roweis, Sam; Winfree, Erik (June 10–12, 1996). On Applying Molecular Computation To The Data Encryption Standard. Proceedings of the Second Annual Meeting on DNA Based Computers. Princeton University.

- Cracking DES – Secrets of Encryption Research, Wiretap Politics & Chip Design. Electronic Frontier Foundation. ISBN1-56592-520-3.

- Burnett, Mark; Foster, James C. (2004). Hacking the Code: ASP.NET Web Application Security. Syngress. ISBN1-932266-65-8.

- Diffie, W.; Hellman, M.E. (1977). 'Exhaustive Cryptanalysis of the NBS Data Encryption Standard'. Computer. 10: 74–84. doi:10.1109/c-m.1977.217750.

- Graham, Robert David (June 22, 2011). 'Password cracking, mining, and GPUs'. erratasec.com. Retrieved August 17, 2011.

- Ellis, Claire. 'Exploring the Enigma'. Plus Magazine.

- Kamerling, Erik (November 12, 2007). 'Elcomsoft Debuts Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) Password Recovery Advancement'. Symantec.

- Kingsley-Hughes, Adrian (October 12, 2008). 'ElcomSoft uses NVIDIA GPUs to Speed up WPA/WPA2 Brute-force Attack'. ZDNet.

- Landauer, L (1961). 'Irreversibility and Heat Generation in the Computing Process'. IBM Journal of Research and Development. 5. doi:10.1147/rd.53.0183.

- Paar, Christof; Pelzl, Jan; Preneel, Bart (2010). Understanding Cryptography: A Textbook for Students and Practitioners. Springer. ISBN3-642-04100-0.

- Reynard, Robert (1997). Secret Code Breaker II: A Cryptanalyst's Handbook. Jacksonville, FL: Smith & Daniel Marketing. ISBN1-889668-06-0. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- Ristic, Ivan (2010). Modsecurity Handbook. Feisty Duck. ISBN1-907117-02-4.

- Viega, John; Messier, Matt; Chandra, Pravir (2002). Network Security with OpenSSL. O'Reilly. ISBN0-596-00270-X. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- Wiener, Michael J. (1996). 'Efficient DES Key Search'. Practical Cryptography for Data Internetworks. W. Stallings, editor, IEEE Computer Society Press.

- 'Technical Cyber Security Alert TA08-137A: Debian/Ubuntu OpenSSL Random Number Generator Vulnerability'. United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (CERT). May 16, 2008. Retrieved August 10, 2008.

- 'NSA's How Mathematicians Helped Win WWII'. National Security Agency. January 15, 2009.

External links[edit]

- Demonstration of a brute-force device designed to guess the passcode of locked iPhones running iOS 10.3.3

- How We Cracked the Code Book Ciphers – Essay by the winning team of the challenge in The Code Book

Smart lockout assists in locking out bad actors who are trying to guess your users’ passwords or use brute-force methods to get in. It can recognize sign-ins coming from valid users and treat them differently than ones of attackers and other unknown sources. Smart lockout locks out the attackers, while letting your users continue to access their accounts and be productive.

By default, smart lockout locks the account from sign-in attempts for one minute after 10 failed attempts. The account locks again after each subsequent failed sign-in attempt, for one minute at first and longer in subsequent attempts.

Smart lockout tracks the last three bad password hashes to avoid incrementing the lockout counter for the same password. If someone enters the same bad password multiple times, this behavior will not cause the account to lockout.

Note

Hash tracking functionality is not available for customers with pass-through authentication enabled as authentication happens on-premises not in the cloud.

Smart lockout is always on for all Azure AD customers with these default settings that offer the right mix of security and usability. Customization of the smart lockout settings, with values specific to your organization, requires Azure AD Basic or higher licenses for your users.

Using smart lockout does not guarantee that a genuine user will never be locked out. When smart lockout locks a user account, we try our best to not lockout the genuine user. The lockout service attempts to ensure that bad actors can’t gain access to a genuine user account.

- Each Azure Active Directory data center tracks lockout independently. A user will have (threshold_limit * datacenter_count) number of attempts, if the user hits each data center.

- Smart Lockout uses familiar location vs unfamiliar location to differentiate between a bad actor and the genuine user. Unfamiliar and familiar locations will both have separate lockout counters.

Smart lockout can be integrated with hybrid deployments, using password hash sync or pass-through authentication to protect on-premises Active Directory accounts from being locked out by attackers. By setting smart lockout policies in Azure AD appropriately, attacks can be filtered out before they reach on-premises Active Directory.

Bruteforce Login Prevention Mikrotik

When using pass-through authentication, you need to make sure that:

- The Azure AD lockout threshold is less than the Active Directory account lockout threshold. Set the values so that the Active Directory account lockout threshold is at least two or three times longer than the Azure AD lockout threshold.

- The Azure AD lockout duration must be set longer than the Active Directory reset account lockout counter after duration. Be aware that the Azure AD duration is set in seconds, while the AD duration is set in minutes.

For example, if you want your Azure AD counter to be higher than AD, then Azure AD would be 120 seconds (2 minutes) while your on prem AD is set to 1 minute (60 seconds).

Important

Currently an administrator can't unlock the users' cloud accounts if they have been locked out by the Smart Lockout capability. The administrator must wait for the lockout duration to expire.

Verify on-premises account lockout policy

Brute Force Login Prevention 2017

Use the following instructions to verify your on-premises Active Directory account lockout policy:

- Open the Group Policy Management tool.

- Edit the group policy that includes your organization's account lockout policy, for example, the Default Domain Policy.

- Browse to Computer Configuration > Policies > Windows Settings > Security Settings > Account Policies > Account Lockout Policy.

- Verify your Account lockout threshold and Reset account lockout counter after values.

Manage Azure AD smart lockout values

Based on your organizational requirements, smart lockout values may need to be customized. Customization of the smart lockout settings, with values specific to your organization, requires Azure AD Basic or higher licenses for your users.

To check or modify the smart lockout values for your organization, use the following steps:

- Sign in to the Azure portal, and click on Azure Active Directory, then Authentication Methods.

- Set the Lockout threshold, based on how many failed sign-ins are allowed on an account before its first lockout. The default is 10.

- Set the Lockout duration in seconds, to the length in seconds of each lockout. The default is 60 seconds (one minute).

Note

If the first sign-in after a lockout also fails, the account locks out again. If an account locks repeatedly, the lockout duration increases.

How to determine if the Smart lockout feature is working or not

When the smart lockout threshold is triggered, you will get the following message while the account is locked:

Your account is temporarily locked to prevent unauthorized use. Try again later, and if you still have trouble, contact your admin.